Not known, because not looked for

But heard, half heard, in the stillness

Between the two waves of the sea.

—T.S. Eliot

To see a World in a Grain of Sand,

And heaven in a Wildflower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour.

—Songs and Ballads, “Auguries of Innocence”

Nowadays, there’s a rain of dazzling discoveries about our universe, many of which offer glimpses beyond the horizons imposed by our supposed order of things. Of course, it wasn’t always this way. For millennia, it was believed the earth was flat and the Sun moved across the sky each day. Then, during the early 1600s, came a convergence of tinkerers and thinkers. They built the first telescopes and microscopes. In 1609, Galileo constructed his telescope after hearing about the “Danish perspective glass.” This enabled Galileo to see beyond the then well-established horizon of understanding to see that Earth is not at the center of the universe.

Another burst of discovery occurred three centuries later, when again there was a consequential convergence of great minds. This coincided with the construction of the Mount Wilson, largest-ever telescope. It was like a colossal climatic pulse point: the human race learned that even the Milky Way is not the center of the universe.

Further along the path to greater understanding came the Hubble Telescope in the early 1990s. Images beamed to earth observers these three decades since have advanced our understanding of the horizon further yet. And, today, our peer into the heavens, aided by both the Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), moves that horizon further out again. As did prior breakthrough technologies, the JWST will surely answer many of our questions, and certainly introduce us to the next horizons. Arising from these advances will be sets of perhaps ever more daunting and, yet, delightful questions.

At each of these inflection points in our understanding, all it has taken to shatter our supposed order of things was a larger telescope (or, for that matter, a more powerful microscope).

Some of what astrophysicists have discovered and delight in these days—while perhaps scratching their heads—is an uppermost limit to what our senses and instruments can perceive: a mere 4.9% of the universe.What about the other 95.1%?

Turns out, there are two impossible-to-detect components to this 95.1%: a mysterious energy component—a whopping 70% of the universe, and a material or matter component—about 25% of the universe. The matter component is equally mysterious. Scientists observe effects everywhere in the sky of “dark energy” and “dark matter” but come up empty-handed when attempting to otherwise detect directly these ever-present realities—even when using their most sophisticated instruments.

Awareness of these realities began that century ago when Edwin Hubble and others spied for the first time into the Mount Wilson Telescope. Quite suddenly, the fuzzy blotches seen through prior (smaller) telescopes resolved to reveal billions of galaxies and colossal clusters of galaxies—each galaxy an enormous system with billions of stars.

Ironically, with this new clarity, a host of unanticipated questions also popped into view. I imagine that, like Galileo and his contemporaries three centuries earlier, Edwin Hubble, Milton Humason (another Mount Wilson astronomer) and others were giddy as school kids with anticipation at each juncture along their shared discovery process.

A few years later, in the 1930s, Fritz Zwicky, one of these inspired astronomers, made a discovery that became an early wellspring for new questions. To Zwicky’s surprise, he observed the cosmos includes colossal, swirling clusters of orbiting galaxies. What’s more, his observation seemed in violation of the laws of gravity and motion, which predict that (whether in solar systems; galaxies or 1,000-strong, swirling clusters of galaxies) the farther away an orbiting object is from a central attracting point, the more slowly the object should move along in its orbit. (Ah, yes, at this realm, we must think of a billion-star galaxy as yet another orbiting object.) However, on the outskirts of these swirling clusters, Zwicky found that the outlier galaxies zoom around in orbits far quicker than their observed mass logically predicts.

The only explanation, Zwicky summed, is that extra, unseen and mysterious matter within galaxies and galaxy clusters is increasing dramatically the gravitational pull toward the center. Otherwise, these objects (entire galaxies) would zip out of orbit. He called this undetectable mass—perhaps unimaginatively—dark matter.

A decades-long controversy regarding this mysterious stuff was sparked and is well worth your Google search for the full story. What I have found to be much more fascinating, however, is the other undetectable reality: dark energy. Not only are our small planet and the Milky Way not at the center of the universe, as it was once believed, our universe is a purposeful process, and dark energy is the name given for the mysterious verve animating it.

Consequently, there has been a century-long, colossal upheaval of how we view everything, if we choose. With each discovery, questions are spawned. One question that pops up (at least for me): Can we now extrapolate and consider our thrill when gazing out into the night sky to be akin to the joy in gazing out across a majestic meadow of seasonal blooms? Dare we conceive of the entire cosmos as yet another buzzing-with-purpose flowering process?

Here’s another question: Is dark energy (dark, as in not seen) that which is expressed in Vijñāna, Prana and Qi.We observe affects or intuit it, but we have no means of observing it directly. Perhaps dark energy is the inescapable yet undetectable “mind” or soul of the universe?

And, along these same lines, what if dark energy is the very same force that cracks open an acorn and gives mind and might to the emerging sprout? What if dark energy is also the very engineer of the oak seedling’s ensuing process towards a sprawling, leafy summertime oasis? What if it’s also the overarching mastermind that guides a tadpole’s transition to becoming a frog, and tells a caterpillar it’s time to spin a cocoon?

Likewise, what if this same invisible force inspires our sermons and songs, our portraits and poems? What if this undetectable energy is the font for supposed miracles (or faith-promoting experiences) presumedly testifying to the truthfulness of one religion over all others? Do these all gurgle up from that same well? When surprised by Nature’s myriad fulfillment processes, is it a privileged peek at dark energy’s zing animating the entire universe’s colossal process?

It’s my sense that many of you readers who are religious are thinking that dark energy is merely the mind of God, and that astrophysicists have stumbled onto what most humans have known all along: God (or Allah or any of the other names given) is omnipotent, omnipresent and omniscient. Beyond the “we told you so,” however, does discovery of dark energy finally reconcile science and religion? Is it that we are all witnesses to the same “soul of the universe?” Does this discovery dissolve divisions and seeming contradictions among faiths and religions, explaining why people of every belief system have faith-promoting experiences? Is it that our use of one moniker or another is incidental primarily to the beliefs to which we were born, the university courses we attended, etc.?

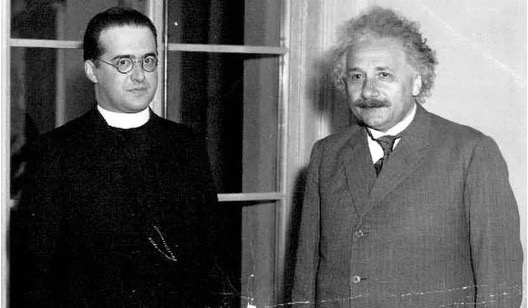

I realize, this may not count for much to many of you but, among the genius astrophysicists of a century ago—whose research gave us the dark energy theory—was Georges Lemaître, (1894-1966). In many ways, he was the preeminent cosmologist during these decades, named the “Father of the Big Bang Theory, and coincidentally a Roman Catholic priest. This bridge across the classic science-religion chasm in one of earth’s consummate thinkers might have become the stimulus for a much broader and sorely needed reconciliation. But, of course, this opportunity seems to have been squandered.

Monsignor Lemaître beside his infinitely-more-famous friend.

Since this discovery era, when Monsignor Lemaître did his pivotal work, the capacity of telescopes to illuminate the next horizon has grown with each new construction. The latest innovation, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), is no exception. The JWST (an instrument we’ve placed into its own orbit around the Sun) was preceded by many powerful telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope (Hubble) which had been earth’s flagship telescope since 1993. JWST has six times the light-gathering capacity of Hubble and is 100+ times more sensitive. It also “sees” different wavelengths than the Hubble does, so that the two are complements to each other.

Seems to me, with our having made such amazing technological strides, we are at a human-knowledge inflection point. Scientists are often privileged to be first to see past the horizon of established beliefs but, thanks to our devices and wireless connections today, do we not all have privileged perspectives, as privileged as Galileo’s, Hubble’s or Lemaître’s in their day?

I marvel at how each form of life I observe—not just human—is driven to thrive. I marvel that each seems absorbed in an individual, vital impulse and process. I marvel at seeds, how they sprout, what they become; embryos, how they flourish; that each is a blossom into individual purposefulness and personality. I marvel that whether from the burst-open of the awakened seed or a moment of conception, a torrent of Élan vital (vital impetus) bathes and conveys each life event. I am in awe each time I’m privileged to glimpse a plant or animal’s inner world. And, no matter where in nature I set my lens—including both microscopic and telescopic—there’s that ever-pulsing drive toward fulfillment.

Of course, I am not alone in noticing this nuance (and I’m assuming you are among us). Often this purposeful drive is called life force, spirit, vital essence, prana (in Sanskrit), Qi or “chi” (the circulating life force that’s the basis of much Chinese philosophy and medicine); Vijñāna, translated as “consciousness,” “mind” or “discernment” in the Buddhist tradition. Seems we might best assume that in each culture and spiritual tradition around the world, we humans are awed by an omnipresent soup of vital essence (or God as love?) in which—when we have tuned in—we find ourselves basking.

It seems to me that when Paulo Coelho championed a “soul of the world” in his masterpiece, The Alchemist, he was hoping to convey the same understanding. Taking this notion one step further, discoveries by astrophysicists this past century might cause us to wonder: perhaps the vital essence that is said to quicken and inspire us so is, in fact, a mere emblem of an elan vital process or “soul” of the entire cosmos? Does vital essence imply process? Further: is my delight authentic when imagining process as a flowering and that perhaps there’s a wondrous purpose to All-of-It: that we, as life at an apex, may once again discover, embrace, find resonance in and thrill to the soul of the universe?